2020-04-17

I’ve added a few features to Pandoc Bash Blog since adding GoatCounter: some cosmetic, some useful, some very behind the scenes.

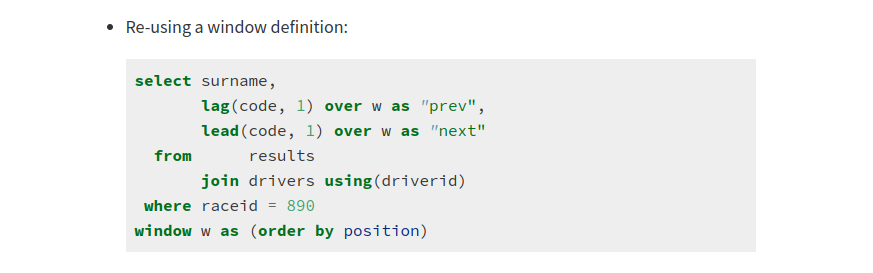

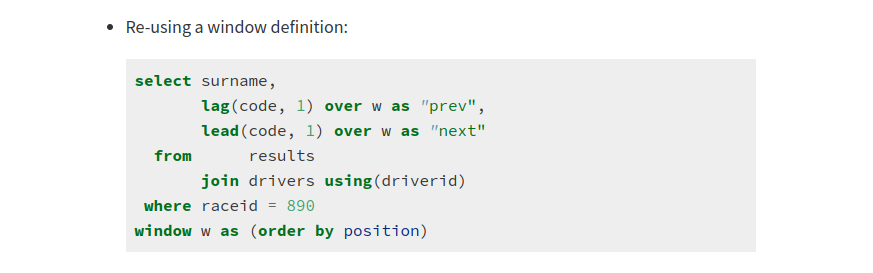

To separate code blocks more clearly from the rest of the text, they now have a darker background colour:

And to tell inline code better apart, it got some colour as well:

I first used the same grey background as for code blocks just like

for example GitHub does for Markdown pages, but bumped into a snag;

pandoc believes that whitespace should be conserved for inline code and

sets white-space: pre-wrap for code. This

preserves whitespace, but still breaks lines; it does leave a blank at

the end of the line, though, and with a visible background colour, that

blank can be seen.

So, a different font colour it was, and after looking at the defaults

for a few CSS frameworks, I settled on #C7254E. Which keeps

the blank, it’s just invisible now.

And finally, because I noticed that my amateur mess of font sizes

resulted in tiny code in headings, I switched everything to relative

font sizes using rems and ems, and in an

exhaustive test of one browser on two screens, nothing looks

fundamentally broken, so I declare that a success.

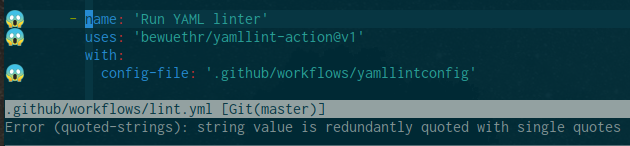

All those actions I wrote when a learned about GitHub Actions have generated quite a pile of YAML files: each action has one for metadata, and each workflow is in one. Since all the actions run on each other, that results in about a dozen or so YAML files floating around.

What’s more obvious than having yet another action to lint these as well? Run yamllint to the rescue!

The action wraps yamllint and works pretty much the same as the Run markdownlint action: the linter checks the whole repo, and an optional config file can be supplied. As for the Markdown linter, I fetch my own from my dotfiles.

Now I just have to update all my files because I recently enabled a new quoting rule…

Anyway, I mention this here because Pandoc Bash Blog uses this action to lint its YAML files.

As a side effect of having grown from very minimal to slightly more

involved, pbb used to make a bunch of assumptions about where specific

files would live. At first, I just symlinked things like the style sheet

from the pbb directory into this blog; later, I updated

pbb init to symlink from the /usr/local

hierarchy and the Bats test setup would actually copy things there.

Now, finally, there is a proper way to install pbb from scratch: a

Makefile! I’m far from a Make expert, but let’s say I have seen worse

than this.

The file is “self-documenting” by way of parsing specifically formatted

comments with Awk, offers a “dev mode” option to symlink instead of copy

things, has an uninstall recipe, and respects the XDG

Base Directory Specificiation. Or at least my personal flavour of

it, combined with a sprinkle of the systemd

file system hierarchy. Everything goes into

~/.local/share (or wherever $XDG_DATA_HOME

points to), and the binary lives in ~/.local/bin, leaving

both $HOME clutter free and allowing for non-sudo

installation.

Since I’m not compiling anything, the Makefile is basically a weird

shell script wrapper, but “use make install” just has such

a nice ring to it.

I did realize that building the blog is actually a pretty good use case for a Makefile—rebuild those pages where the Markdown version is more recent—but that ship has sailed. Bash it is.

The TAOP summary is pretty long, so I thought it’d be useful to have a table of contents. pandoc can create one, but I wanted it to be easy to control. There are a few knobs to turn, but I eventually figured out the correct ones.

Initially, I thought I can use either of the toc or

table-of-contents metadata fields and set them to

true in the YAML header of the post I want a TOC for. That

didn’t work.

I was confused about the meaning of the variables. A glance at the default HTML template made things a little more clear:

$if(toc)$

<nav id="$idprefix$TOC" role="doc-toc">

$if(toc-title)$

<h2 id="$idprefix$toc-title">$toc-title$</h2>

$endif$

$table-of-contents$

</nav>

$endif$They’re all different! toc serves to indicate if the TOC

should be printed at all; table-of-contents actually

contains the TOC. Aha. Setting toc: true in my

post did give me an empty <nav> tag, but the table

itself was missing.

As it turns out, the toc metadata variable and the

--toc command line option are different as well.

--toc is required to generate the table, and the

toc variable controls if it is displayed or not. But now I

got the TOC everywhere, and I wanted the default to be “no TOC”!

The last puzzle piece was to use a metadata

file where I can set toc: false so the default is to

not have a TOC; if I do want one, I can override the value in

just the post where I want it. This also let me customize the heading

used for the TOC by setting the toc-title variable.

Or at least that’s how I think everything works, but who knows. This post uses a TOC, just to show what it looks like.

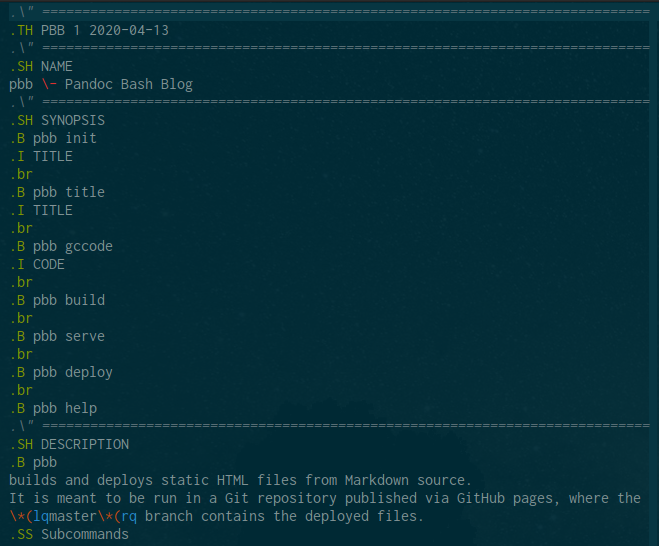

Last, but not least, pbb now has a proper man page. It’s officially the official source of truth, other than the code itself, that is.

Not everybody considers writing documents using the man

macros for roff exactly “thrilling” or “fun” or “not a

waste of time”, but I kind of like it. It’s a bit like Markdown’s

great-great-great-grandma! I keep hearing about mdoc being

all the rage (mostly when I read anything written by its author) and

“semantic” instead of just “presentation formatting”, but whenever I

think of it, I’m already halfway through whatever I’m writing and

promise myself to check it out next time.

I try and follow the Linux man page conventions as outlined by man-pages(7)

regarding structure and style; the man page for the man

macros man(7)

and its longer cousin groff_man(7)

come in handy to remind me of how to start a paragraph with a hanging

tag (.TP!) and how to get pretty quotes (\*(lq

and \*(rq!); the GNU roff short reference groff(7)

is useful for all those non-man requests (new line?

.br); and finally, if all else fails, there’s always the

full-blown GNU

troff manual.

There surely are a lot of man man pages.

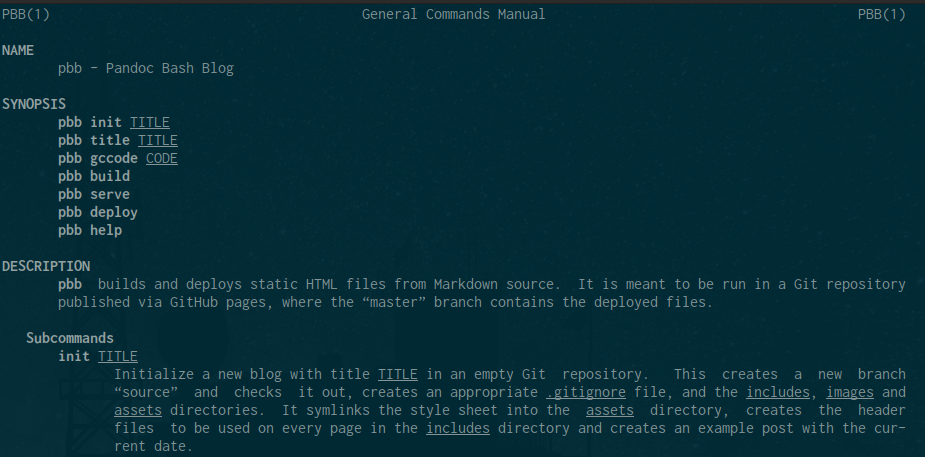

In the end, all that counts is that going from this

to this

is super satisfying. To me.